The Golden Age of the Carpenter.

BTG member Kev Bower has worked on some really unusual projects, here’s his take on what it’s like to work on more traditional jobs, where master craftsmen are keeping the skills alive…..

Walk onto any modern-day construction site and you’d be forgiven for thinking that the golden age of the carpenter is dead. You’ll find prefabricated roof trusses, plastic and aluminium windows, acres of isocyanate foam sheeting, principal joinery components in factory-machined, factory-primed MDF, doors moulded from laminate and cardboard…. the list is endless. But for every modern build, there exist ten times that number of structures which date from before 1930 and countless others whose construction dates wind back many hundreds of years before that – right back through the pages of history. Fortunately, there also exists a substantial band of skilled craftsmen who dedicate themselves to the restoration and upkeep of these buildings, many of which are architectural gems, the fabric of our very heritage.

This type of conservation and listed-building work is often painstaking and time-consuming – and therefore inevitably costly for the customer. It can be incredibly frustrating to deal with the plethora of red tape and regulation-driven ‘treacle-wading’ which often accompanies this type of project – along with occasional bouts of open-mouthed horror at seeing plans rejected for potentially stunning, heritage-sensitive restoration work (done so that it looks like it’s always been there) – only to see planning control giving the nod to a huge steel and glass carbuncle bolted to the side of an ancient building. But when it all comes right, you can stand back looking at what you’ve built, confident in the knowledge that it’s beautiful, and that it will be there for generations to come. The sense of reward can be truly immense.

I’ve been lucky enough to have been a part of all this for as long as I can remember, and although I could probably fill several entire websites with stories and photos, for this short piece, I’ve focused on the old premise that ‘you’re only as good as your last job’ – which ended just last week on a sunny day in a little hamlet near Rennes in north-western France. A long-standing English customer of mine – already the owner of two historic French properties which I’d been privileged enough to work on – had recently acquired a stunning (but virtually derelict) cruck barn dating from the 16th century, and he was in the process of making it wind and watertight – which firstly meant a new roof to sit atop the fabulously intact cruck frame, and all to be hand-built using centuries-old methods, under the watchful gaze of a stern French conservation official.

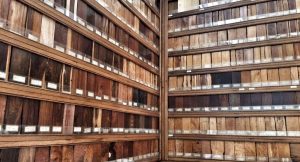

The first job was a visit to the official’s office carrying samples of all the timber, to ensure that the colours and textures exactly matched the breathtaking collection of historical samples on his office wall display case. They did!

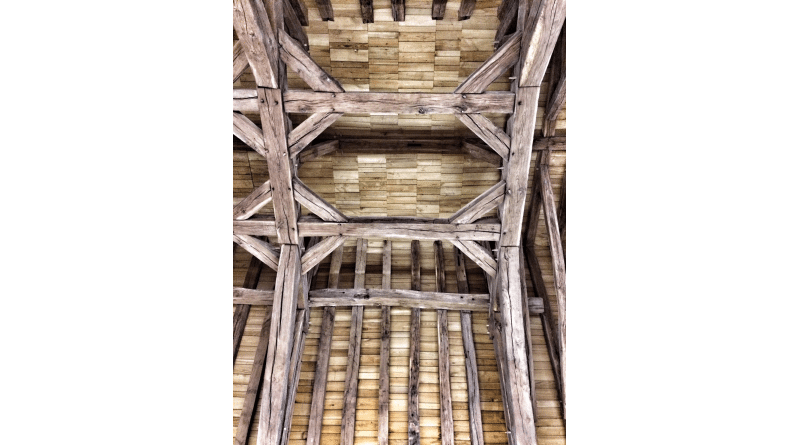

So what you’ll see on the attached photos is my part in this – the application of a historical sarking technique known as ‘morcellage’. These relatively short, random sections of sarking timber were cut and fixed this way for two reasons – firstly, during the early post-framing stages of the build, horse-drawn wagons would arrive laden with young trees which had been locally harvested the previous year and had spent a year drying out. Elm, oak, ash, plane, larch, pine, sycamore – essentially any species which was growing nearby. These would be hand-sawn into planks around an inch thick, and of random widths and lengths according to the dimensions of the tree.

The second reason for this technique was that the traditional roof tiles of this period were known as ‘tuiles plats’ – these were elongated clay plates with a gentle curve along their length which had a hand-moulded projection on the base called an ‘ergot’ which was used to hang the tile on battens, usually made from poplar. But early firing techniques meant that the ergots would often fail prematurely, and the tile would slip. So morcellage – the use of these numerous short sarking timbers – conveniently allowed a tile to be replaced from below, simply by removing a few timbers and ‘wiggling’ a replacement tile into place through the hole, before re-fixing with lime mortar. A good idea – especially when you see the height and impossible pitch of some of these ancient roofs.

It was hugely rewarding to work alongside a fourth-generation French traditional roofer, using reclaimed tuiles plats from the region – and equally satisfying fixing these sarkings in place using exquisite traditional flat nails, hand-forged by a local artisan – and in particular – a great honour for a humble Englishman.

Kev Bower,

Carpenter.

Some amazing pictures , great work!

Great read Kev, you have been fortunate enough to get and produce some quality work only some can dream about. 👍